Wordsmith or Storyteller: Embracing Your Identity

Read Mr. Schwabauer’s first post on finding your identity as a writer »

Writers tend to be predominately either Wordsmiths or Storytellers. Recognizing your own tendencies is not a magic formula for writing success, but it can be enlightening.

Wordsmiths tend to focus on images created by words and phrases. They love the sound of words, the texture words create in the mind. Wordsmiths will go back and read a certain passage from a favorite book not just because of how it works as a story or how emotive it was the first time, but because the words sound so cool the way they’re arranged. Wordsmiths typically describe things in glorious detail, but struggle to give those details meaning.

If you’ve ever written something you loved without really knowing what it meant, you probably have wordsmith tendencies. Wordsmiths are image people.

Ray Bradbury, for example, is a terrific wordsmith. Here is a single sentence from the first page of “All Summer in a Day.” Note the images.

“It had been raining for seven years; thousands upon thousands of days compounded and filled from one end to the other with rain, with the drum and gush of water, with the sweet crystal fall of showers and the concussion of storms so heavy they were tidal waves come over the islands.”

Storytellers, on the other hand, tend to concentrate on the concepts and ideas that make their stories work. They’re more concerned with the idea of a story than its execution, and may struggle when trying to convey believable details. Their inner world may be rich and beautiful, but they find it hard to zoom in on any particularities.

Storytellers often invent great story concepts but then drop them early in the writing process. They have fewer problems torturing their characters or finding interesting plot twists, but their prose tends to be written in summary mode—using concepts.

People who rarely read a book more than once (because they already know how it ends) are storytellers. Put simply, storytellers are concept people.

The opening of Saki’s “The Interlopers” is a great example of a storyteller setting up a tale through concepts. He relies on generalities and passive verbs (both of which I’ve highlighted) because he’s far more concerned with the story concept than with the particular details of setting and description. This story works not because he is using great details (he isn’t), but because he’s using a great concept. The last sentence in the first paragraph is a terrific example of storytelling.

“In a forest of mixed growth somewhere on the eastern spurs of the Karpathians, a man stood one winter night watching and listening, as though he waited for some beast of the woods to come within the range of his vision, and, later, of his rifle. But the game for whose presence he kept so keen an outlook was none that figured in the sportsman’s calendar as lawful and proper for the chase; Ulrich von Gradwitz patrolled the dark forest in quest of a human enemy.”

It’s important to understand that no writer is purely one or the other. To some degree we’re all both. And were both because whichever tendency we have, we still have to translate our imagined story events into both concepts and images. The conversion process is identical, regardless of which type of writer we are. What differentiates us is the ease with which concepts and images spring up in the imagination.

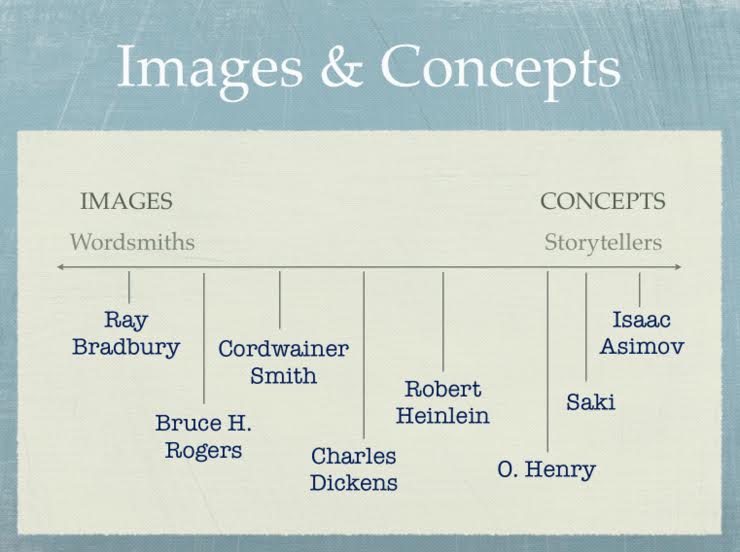

Put this way, it is easy to see the concept/image tendency as a sliding scale. Here is where I would place a few well-known writers on this scale:

You may disagree with the exact placement, but I’m guessing you agree that Ray Bradbury belongs more on the image side of the scale than the concept side, and that Isaac Asimov is just the opposite.

Recognizing your own tendencies regarding images and concepts can be very helpful in sorting through the initial stages of writing.

WORDSMITHS

If you’re a wordsmith, you probably get too excited about mediocre ideas because it doesn’t take much for your brain to start feeding you cool images. This is why you can write a 400-page novel only to discover at the end that you don’t really know what you’ve been writing about. (Don’t ask me how I know this.)

You write best when you discover a great concept on which to hang your amazing details. Take the time to iron out your ideas before you begin. Eventually, you may develop the Bradbury-like ability to begin writing off a single image and continue until you have ferreted out its meaningful story. But that skill takes time and practice.

Therefore:

• Slow down. Take time to examine your images.

The first image you see is not always the most powerful one.

• Expand the images. What else do you see?

What might be there that you haven’t noticed? C. S. Lewis saw a faun with an umbrella.

• What emotion is connected to the images?

What did you feel when you first read the lamp post scene in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe?

• What meaning does that emotion point to?

This will give you a hint about where your story is really coming from.

• What structure does that meaning derive from?

You’re working backwards to find the story, the meaningful conflict.

STORYTELLERS

If you’re a storyteller, your weakness will be finding too many concepts that rely on fuzzy, ambiguous or incomplete details. The cool story in your head will not be as cool in the reader’s unless and until it is fleshed out.

As a storyteller you should pick those story ideas that are linked to unusually clear movies in your imagination. Concepts are usually born flawed.

Therefore:

• Examine your ideas for originality.

What makes your idea unique?

• Combine at least two unexpected ideas.

This intersection of ideas is usually where you will find the real story.

• What emotion does this combined idea create?

A story without emotion is not a story at all.

• What meaning does that emotion point to?

What is the significance of the emotion and its connection to your story idea?

• What structure does that meaning derive from?

You are working backwards from disconnected ideas to find a meaningful conflict.

…

Where would you place yourself and your favorite authors on the sliding scale? Does taking note of your area of strength help you write?

…

Daniel Schwabauer, MA, is the creator of The One Year Adventure Novel and Cover Story Writing creative writing courses. His professional work includes stage plays, radio scripts, short stories, newspaper columns, comic books and scripting for the PBS animated series Auto-B-Good. His young adult novels, Runt the Brave and Runt the Hunted, have received numerous awards, including the 2005 Ben Franklin Award for Best New Voice in Children’s Literature and the 2008 Eric Hoffer Award. His third book, The Curse of the Seer, was released in the summer of 2015.

I am definitely a storyteller. No doubt about it. I think that’s part of why I struggle so much with writing. I have so many ideas, but when I sit down to write, my writing doesn’t always come to life like it should.

I remember talking in my Shakespeare class about how Shakespeare was a wonderful wordsmith, but not much of a storyteller at times. Having read this article, I wonder if maybe this is why I don’t connect with Shakespeare’s work as much as some of my classmates/friends…

I seem to be in the middle,

”This is why you can write a 400-page novel only to discover at the end that you don’t really know what you’ve been writing about.”

I have done that, (well, not the 400 page part, yet) and do it often. But most of the time I lean more to Story Teller.

Thanks!

I think I might be close to storyteller but not quite I know I can see the big picture but certain details evade me, but in a way I can almost see the details just putting to words is the hard thing.