Practical Steps to a Rewarding Fantasy Map

By Tineke Bryson, Staff

How do we make our story world maps the best they can be? After tackling intimidation, and coming to terms with the risks we take by not actually drawing our fictional world, how do we actually make the map?

…

It’s easy to wax poetic about maps of fictional places. They are just so exciting! But nailing down a list  of practical steps for getting the most out of our mapmaking projects is tough. Lists are, well, limited. This post can’t say everything.

of practical steps for getting the most out of our mapmaking projects is tough. Lists are, well, limited. This post can’t say everything.

Here’s what I’ve got.

1. Think about your map’s purpose.

Is this map primarily to help your reader get situated? Or is it for you as the writer? It may seem rudimentary, but we need to consider our audience. How much information do our readers need? It’s okay for a map to be mainly decorative, but if we want our readers to use the map, we’ll want to make it approachable, which means easy on the eyes.

Deciding to have the map figure in your plot itself can be a great way to heighten your reader’s sense of being along for the adventure. There’s also something compelling about a map that purports to have been made by a character’s ancestors, or, say, a group of mysterious underground historians. But if we want our readers to buy the idea that the map is an ancient artifact, or a copy of the original map in the hands of the hero, we have some work to do. It’s got to look the part. If it’s supposed to have been scrawled by an uneducated hillbilly, it certainly shouldn’t sport sophisticated nautical bearings.

It’s also got to contain the information the characters themselves reference, and shouldn’t it also be in their script and language?

But I don’t have that language worked out! And if I put it in their writing system, my readers won’t be able to read it!

No worries. Tell your readers it’s a translation from the original. Seem underhanded? You might be surprised how often writers use tricks like this. If you create an illusion of distance from the source, you lift the pressure to make it perfect.

Tolkien makes liberal use of this distancing maneuver so that he can include elven poems and songs in his books. By telling us, through Bilbo or Sam, that “this is a translation,” he is able to convey the sublime idea of the piece without undermining the effect—never mind his credibility. After all, if you say an elven song is otherworldly and full of mysterious power, you can’t exactly put stilted words into their mouths.

2. Choose materials.

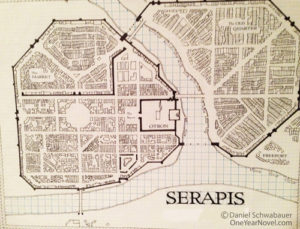

Your vanished paleontologist mentor figure may well have etched his maps in leather, but you probably don’t have that option. What will you use? Daniel Schwabauer—Mr. S. to many of you—likes to use large sheets of graph paper because it’s useful for scaling. If that’s not an important concern, any blank paper will do, but large sketching or art paper is the best.

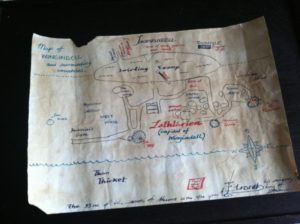

It’s especially fun to prep the paper for your final product by staining it with wet black tea bags and sticking it in the oven on medium heat to speed-dry. You do have to keep a careful eye on the paper—remove it when the edges begin to curl. It comes out looking hundreds of years old (okay, not really, but close). You can flatten out any warps in the paper by ironing it on low afterward.

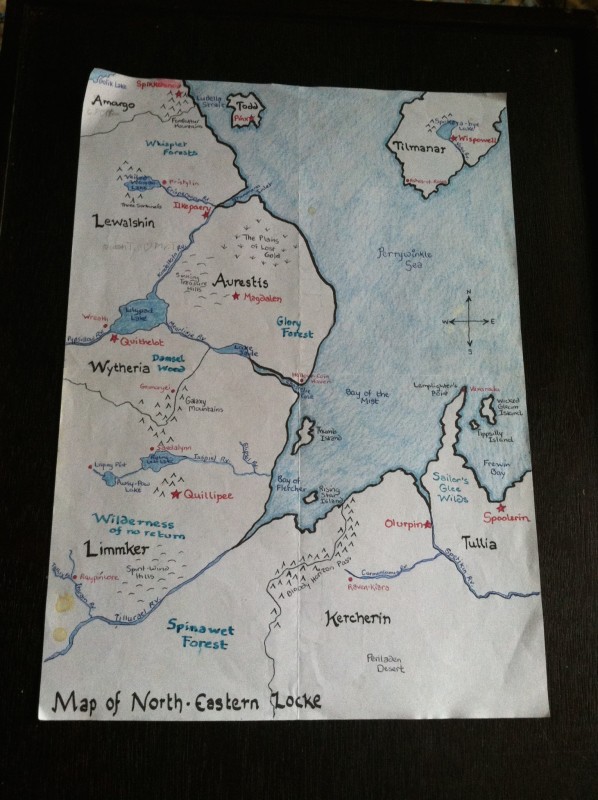

Here’s an example of a tea-stained map. I made it when I was 11, so, you know, I stole a lot of place names from Middle Earth. 😉 FYI, since I only decided to blacken the edges AFTER drawing the map, I was overcautious with the matches, so this is not a great example of the match technique.

For an extra touch, hold a lit match to the edges and carefully blacken them. It’s a good idea to have several pieces of dyed paper ready, since putting a match to them is an imprecise art. Some of them will turn out cooler than others.

As far as what to draw with, it’s always a good idea to sketch in pencil first, of course, but when you’re ready to finalize, just make sure you use a pen you know you can depend on, and that you have extras in case it gives out. You want your lines to be consistent and clean.

3. Seriously consider taking up calligraphy.

Calligraphy pens revolutionized my maps when I was in my teens. Before I got this calligraphy kit, I really thought beautiful writing could only be achieved by a mysterious magical art. Then I learned that it’s all about the pen. Calligraphy takes some practice, but if you would like to add some seraphs and style to your lettering, I would seriously recommend getting a basic kit. It’s fun, and it makes your words look awesome.

4. Make a decision about scale.

We talked about the option of actually using a scale for our maps in our last post. It’s very useful for determining distances your characters need to cover. Of course, there’s a certain freedom in drawing without one, but even if you prefer to set aside practical considerations when first drawing your world, you can add a scale in the revision stage.

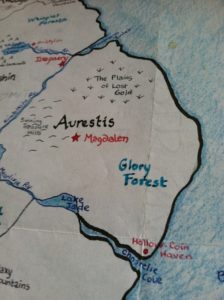

Example of where NOT to locate the biggest city in your trade-loving country, courtesy of 9th grade me.

Just do yourself a favor and make it simple to compute. In my 9th grade fantasy world, for instance, a tol was equivalent to half a kilometer. I’m not good at math, so I don’t pressure myself to reinvent the wheel.

Distances are not as complicated as we may imagine, and the Internet is full of information. Need to know how far the average person can walk in a day? Look it up. Need to know how fast a horse carrying a human can gallop? Look it up.

5. Let the geography teach you.

We addressed geography and culture at some length in our last post, but to sum up: Anyone who’s studied history or culture knows geography directly impacts culture. A people group isolated by mountain ranges is unlikely to feel friendly to strangers. A kingdom without a coastline is likely to resort to violence to get access to a port. Or focus its energies on trading agreements with coastal neighbors. If your story world boasts an advanced civilization in the middle of a wasteland, you’ve got a lot of explaining to do.

6. Name away, but reign your taste in with reason.

One of the most intimidating aspects of mapmaking and of world building in general is naming. We long to be creative—to draw the reader in with enticing-sounding place names and characters—and yet we also want to be consistent and grounded.

I am not a place names genius. Half of my first story map was stolen straight from Middle Earth (see photo of my tea-stained map above). When I grew older I named places with reference to a long list I kept of all my favorite words. Isolating all the best syllables, I mixed them up and put them together in new combinations. Quilt and teepee turned into Quillipee; Spoolerin River was just an elaboration on spool. When I needed something ugly for naming enemy territories, I did the reverse. Since many of my favorite words happened to be Anglo-Saxon (or from Tolkien!), this gave my kingdoms a unified feel, but that was as deep as my linguistics went.

Other writers, my husband for example, go to more trouble. In creating a kind of alternate plane version of the pre-Medieval British Isles, he studies the makeup of British place names by region and plays with the roots for his own combinations. He carefully avoids any root words with Latin influence because they would be anachronistic.

Remember, pick names that are sensible—that spring from the commonplace—instead of names that drip with innovation. Remember to use reason to work out what kind of names would actually make sense.

In the real world, even gorgeous, epic-sounding place names are based on prominent landmarks or flora and fauna, or important people, or historic events. They only sound mysterious because they are in a language or dialect you don’t know and you are unfamiliar with the area’s history and geography.

The way to make your fictional world believable is to give names in the same way. It may seem humdrum or too much hard brain work, but when you hear your readers use those names with a straight face, you better believe you’ll be glad you grounded your world in reality.

The easy tricks to naming imaginary places and people may seem cheap. But even Tolkien started with what he knew about languages and cultures in the real world. J. K. Rowling gave names to her fictional magical spells by vaguely Latinizing related English words (e.g., winguardium leviosa, a charm to make an object or person lift off the ground, is roughly named for “lifting” and “wings”).

It’s better to make modest attempts at introducing new words and language than to bite off more than you can chew. Don’t jerk your reader from one unfamiliar, difficult-to-pronounce name to the next. If you want to use an invented term, make sure to first use it with context so that your reader can add it to their vocabulary without confusion.

7. Give yourself a break.

No one has ever mapped your story world before. Instead of daunting you, this should give you courage. There isn’t one right way to do it. And you don’t have to worry about someone else outdoing you—not unless you make it big; and by then your happiness about being a successful author will make your more artistic fan’s astounding map less of an affront.

So… have fun. The most beautiful maps all started as scrawls. The most impressive world-building started with jotted notes and quick sketches.

…

What tips or practical steps would you add to this list?

Awesome post, Tineke! I’ve thoroughly enjoyed this series, and this post is great! You’ve given me good tips for revising my map and making it much better. Thanks!

I am glad! Thank you for faithfully reading! These have been fun to write 🙂

Thanks for all these tips about maps they are really useful!

You’re welcome, Clare!

I have really enjoyed all three posts in this series. You have now inspired me to make a map and think of sensible names to put on it. 😛 Thanks for the boost.

It’s interesting that many people find the idea of “being sensible” deflating. Personally, I find it really encouraging that even the most amazing fictional worlds are built on common sense, not just inspiration. Because if it takes down-to-earth thinking, that’s something I can actually DO!

Thank you for reading, Hannah!

As for other steps, I’d say that it’s perfectly fine to rethink and redo your map if you don’t like a previous one that you’ve made. You’ll learn about your world through mapmaking and if there’s something missing, you can change everything around to add that aspect in (depending on how important it is).

If at first you don’t succeed, try and try again.

For a recent writing project, I stole most of my place names from real towns and villages in Britain. Google maps can give you some really cool names to use!

This is the coolest site and your writing is superb and so enjoyable to read. I have made maps for my unique story world Azaria but you have convinced me to dig deeper on that world and to have fun. You also convinced me to map my romance trilogy/wip. Thanks so much!

Over at worldspinner.com, we also espouse using maps as a prop as part of the story. I also find that they then scrutinize that map for more clues than you initially intended, leading to other story ideas too.